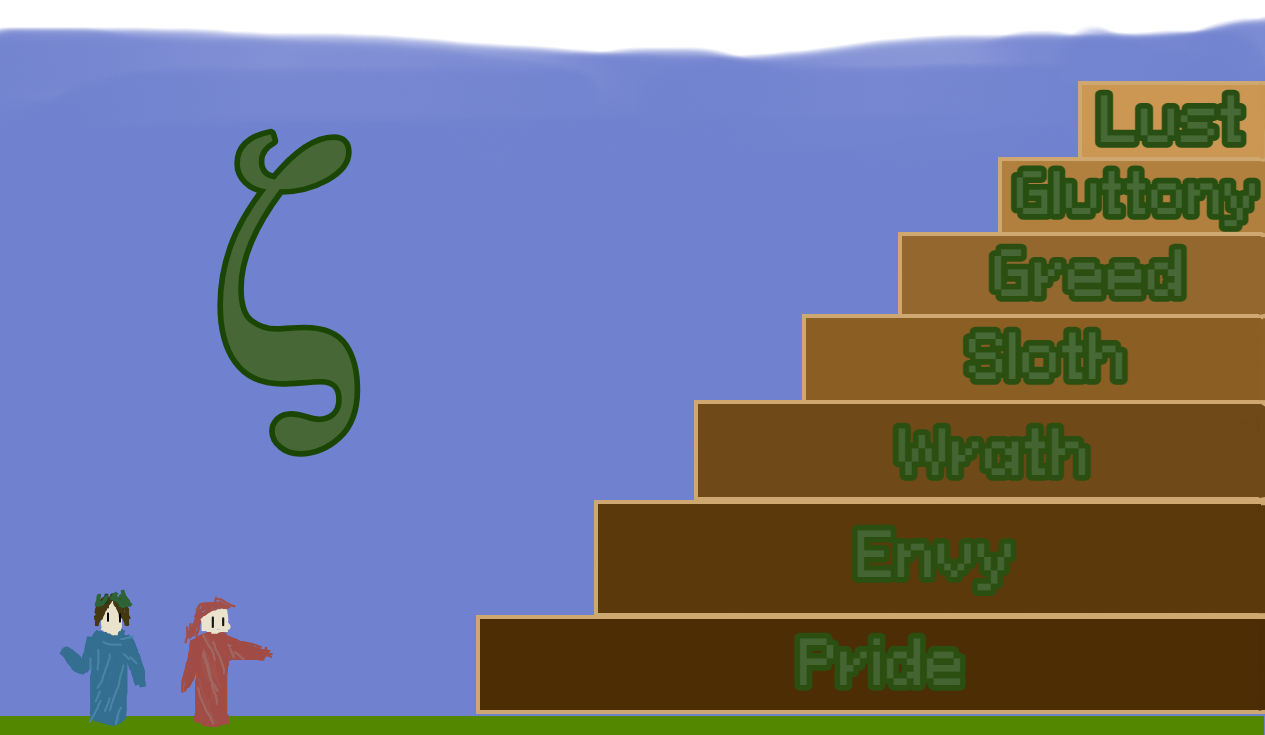

The 7 Sins of Discourse

The seven deadly sins are a unique cultural touchstone. They’re seen in anime, games, and even spite-driven biblical fanfiction. An interesting thing to note is that all seven are essentially base urges or impulses. They can be harmful in excess or under the wrong circumstances, but still have functions essential to healthy lives. I’ll come back to that later.

The state of discourse is rather pitiful online, especially in arguments surrounding zoophilia. It’s apparent that many engage in discussion with poor etiquette and logic. As such, I thought it would be interesting to use this influential set of vices as a lens to examine debate methodology through, in the hopes that we can identify and counter these vices more effectively in ourselves and others.

Lust

In a literal sense, lust is sexual desire; it can also refer to any desire, such as a “lust for life” In modern psychology, lust is understood as a normal emotion which many people experience. The problem arises when one puts their own desires over another’s will, objectifying them in the process.

In a zooey debate context, this can manifest as objectification of non-human animals. While it doesn’t imply *literal* lust on the part of the , it indicates an unwillingness to consider the autonomy and personhood of our companions in the pursuit of an intellectual victory. Arguments based on argumentative lust reject the first and second ZETA Principles and are therefore irrelevant to us; I doubt animal objectifiers would wish to be treated as objects, and the wellbeing of the objectified is inherently given less consideration.

More broadly, this concept can encompass any time an ideological opponent is objectified in an argumentative context. This includes viewing them as a target or enemy rather than as a person, as well as a wide array of dehumanizing ad hominem attacks. One cannot hope for a fair fight when one is mistaken for a training dummy.

Gluttony

Since gluttony and greed are essentially equivalent in terms of overindulgence, I’m going to cheat here and take a page from The Screwtape Letters. In it, C.S. Lewis defines two kinds of gluttony, appetite and delicacy. We are all familiar with the hedonistic, excessive approach of the former. The latter is essentially a form of selfish pickiness which insists on an incredibly specific meal, yet is never satisfied.

In debate, this is analogous to having a voracious appetite for counterpoints– except nobody can seem to find any that count. This is also called “special pleading” which is when a principle that is agreed to otherwise apply is discounted without merit for a particular argument. For example, may concede that a horse is perfectly capable of letting a human know whether they are comfortable being ridden. However, in the context of a zooey relationship, they unjustifiably assert that a horse's ability to communicate is insufficient. This doesn’t flat-out reject the literal mountains of evidence which show interspecies communication is possible. Somewhat more insidiously, it reinforces outdated ideas which put relationships and intimacy onto pedestals, high above other forms of interaction. The reality is that they are just other categories of bonds and activities that individuals can agree to participate in.

Greed

Avarice is the time-honored tradition of hoarding and engaging in extravagance. Its usefulness as a survival strategy can easily be attested to by animals such as squirrels, who gather as many nuts as they can to survive the winter. It becomes maladaptive when it becomes unreasonable and One personification of avarice is Prince John from Disney’s Robin Hood, a furry staple. His heavy taxation sends his citizens to jail, where they do hard time and hard labor in equal measure. No matter how much wealth such a person has, it is never “enough” for them. As a consequence of setting such ridiculous standards, they devalue everyone’s earnings and work.

In discourse, this can manifest by someone demanding “enough” proof from us that our relationships are ethical and real “enough” for them. No matter how many studies and anecdotes we may shovel into their gaping maw, they demand more. This is distinct from Pride in the sense that they aren’t discounting our sources altogether; they are simply saying the quantity is lacking. They might claim the burden of proof is on us and that they will be unconvinced until certain (usually rather lofty and unrealistic) conditions are met. This particular vice is harmful because it places an undue burden on our already taboo and understudied communities, all for the validation of a single unqualified individual, held tantalizingly out of reach. Through a sort of intellectual inflation, it demeans our sources and arguments through demanding such a high quantity.

Sloth

Although typically characterized as laziness, I would argue that the root cause of sloth is usually either exhaustion, apathy, or poor focus. If you are out of resources, uninterested, or can’t focus, you likely won’t get much done. Reframing laziness as a symptom of an underlying issue would be beneficial to many people. However, when someone goes out of their way to engage in discussion and evokes sloth, this can be harmful. It demeans the subject by failing to engage with intellectual integrity and vigor.

People do this by repeating themselves, making claims without supporting them, engaging in gish-galloping and what-about-isms, and generally employing leaps of logic. Gish-galloping and what-about-isms are characterized by asking a great deal of somewhat unrelated questions and changing subjects frequently in order to avoid deep or meaningful discussion. It’s a strategy which is the intellectual equivalent of spiders having thousands of children; the hope is that a decent portion will remain undefeated due to the sheer quantity. These forms of arguments are pretty easy to call out and dismiss once you notice them, but they can also be pretty exhausting if you decide to take the high road and confront each point in good faith.

The uniting characteristic of all of these strategies is that they require little thought to make, but take a lot of work to counter. An unsupported claim can easily dominate conversation if it’s taken seriously. Leaps of logic can take a whole day to untangle if you don’t use the Gordian method of slicing it apart. Of course, those who use these strategies, whether intentionally or not, often disagree that their arguments are fallacious. So you’ll also be given the burden of proof for that, too.

If there’s anything anyone takes away from this, please remember not to be intellectually lackadaisical; you’ll just blend into our wretched surroundings, like a moss-covered sloth in the rainforest… who’s cursed to immobilize anyone who touches them (the analogy still sounds too cute, but you get what I mean).

Wrath

This is an easy one to spot. Wrath is prevalent online, especially on Twitter. Use of ad hominem (personal attacks) and rage-baiting are not proper arguments; they’re emotional appeals intended to discredit the recipient. In a broader sense, overreliance on preconceptions and gut feelings can also be included here. Both are shallow forms of engagement based purely on emotion. Neither actually confront any arguments in a meaningful way. It’s usually either incredibly thinly-veiled harassment or simply a willfully ignorant opinion. It’s probably best to either disengage, call the perpetrator out, or joke a little back. A pretty good example would be that time an said none of us should be on the planet, but they misspelled it as “plant” The meme since has acted as a retaliatory morale boost.

Most examples of wrath are less amusing and more damaging. By calling us abusers, monsters, etc. and leveraging all kinds of horrible threats against us, are perpetuating stigma and hasty generalizations rather than backing those up. The bullying wouldn’t be any more acceptable if they *could* corroborate their base assumptions, but the fact that they don’t stagnates the discussion while also leaving it smoldering.

Emotions do have a proper place in arguments, such as citing our love for animals to assure concerned onlookers that we are not malicious, or appealing to emotions by discussing the horrible atrocities committed against other species and their anthropocentric justifications. The difference is that personal attacks, trolling, and dogmatic zealotry are irrelevant, unconstructive, and unyielding; ideal discourse requires civility and integrity from both sides to flourish.

Envy

This is a tricky one to pin down. Traditionally, envy means that one wishes for something or someone which another has. This by itself doesn’t do any harm, and it can be argued that envy is an important motivator towards societal change and individual improvement. In argument, however, I would postulate that it represents a willingness to sabotage the opponent’s points. Metaphorically, the envious party wishes for arguments that will overcome their opposition, so they rig the line of reasoning.

One method of subterfuge is defining key terms in such a way that one cannot lose. Some may recall the time in which a defined informed consent in such a way that it necessitated shared humanity, but their reasoning was nebulous and circular. This is the essence of what I mean by sabotage. Whether intentional or not, they set up the argument so that nothing could be learned or challenged. They began and ended with their definition.

The harm in this is that it puts words in our mouths, makes assumptions about what we mean, and stubbornly presents the conclusion and initial claim as synonymous. Unlike those guilty of pride or wrath, the perpetrator can come across as genuinely seeking debate, only to undermine it every step of the way. Inflexibility in the guise of openness does not produce constructive discussion.

Pride

Aside from wrath, this is probably the most common vice we contend with in debate. Maladaptive pride is synonymous with arrogance– seeing oneself as superior to others and disregarding their stances, knowledge, and objections as a result. It fundamentally means that no matter what points a prideful person is presented with, they will always consider themselves victorious. In this sense, pride is egotism combined with cognitive inflexibility; why challenge one’s views if one is already believed to be superior?

Specifically, refusing to concede or give credit where it’s due are both key signs of arrogance. Part of this, in my opinion, often comes down to a genetic fallacy, which claims the veracity of a statement is equal to the perceived credibility of its source. We are fully aware of how most people– including – see us; in many cases, they may reject what we say simply because we’re the ones saying it. This calls into question the relevance of the ZETA Principles and this very magazine when conversing with individuals afflicted with the genetic fallacy. They dismiss our points because we’re the ones making them, so what are we to say to them? We may as well be speaking to dogmatic brick walls. Perhaps they can be eroded over time, perhaps not.

They do serve as an important object lesson, however; if we do not wish to be prideful towards others, we have to listen to them and consider their points. We need to acknowledge when they’ve made a solid argument or at least when part of their argument comes from an understandable place. Nobody likes to be dismissed or ignored. Unfortunately, those who need to reflect on this would likely not deign to read it.

Conclusion

There are far more than seven ways to engage poorly in discourse, but the above best fit the sinful theme and are all noteworthy in their prevalence and propensity for instilling frustration in even the most mild-mannered of us. Some of these vices may be more effective on some of us than others, and some of us are more adept at recognizing these maladaptive strategies. Hopefully by listing them and explaining why they’re wrong, more of us will be able to join the latter ranks. As an added bonus, it gives us the opportunity to reflect on our own conduct and determine how we can improve.

One final note: As I mentioned earlier, each of these sins has a purpose if used properly in moderation, and abstaining completely can be just as harmful as indulging excessively. A pinch of lust/sloth can help you distance yourself from your opponent so you aren’t susceptible to wrath. A sprinkle of greed/pride can counter the opponent’s slothful tendency to leave claims unsupported. A dollop of gluttony can distinguish a category from its ilk and, if supported, defeat hasty generalizations. Controlled wrath can let the opponent know you’re not messing around. A grain of envy allows us to define our own terms so we can speak about our experiences and values. It’s all about extent, technique, and context; the descriptions throughout this article are examples of how *not* to use these essential tools in debate, at least in my opinion.

Of course, any corrections, clarifications, or opposing views are welcome to challenge my assertions. The only pride I have is zoo pride.

Article written by akesi Kuwa (April 2025)

Find the ZDP RSS feed link in our footer any time you're on the website! That url for anyone interested is https://zooeydotpub.org/feed.xml

Questions, comments or concerns? Check out our Discord server! discord.gg/EfVTPh45RE